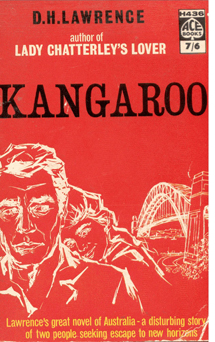

The

1962 Ace edition of Kangaroo

- showing the Sydney Harbour Bridge 10 years before it

was built. This paperback edition was clearly a cheap

effort to cash in on the success of the Lady

Chatterley

court case in London, which had the effect of allowing

Lawrence's best-known work to be legally published.

THROUGHOUT

THE 70s, 80s, 90s and well into the new century, the prime

suspect - the main focus of our research - was Jack Scott.

There was no question in my mind - and in Andrew Moore's,

too - that he was the main source of Lawrence's information

about the secret army. (I think John Ruffels was also

convinced of that, as was of course my wife and co-conspirator,

Sandra. To give him credit, I believe that Joe Davis now

also thinks this.)

Jack Scott was almost certainly the principal Australian

character in Kangaroo. He was the sinister Jack

Callcott - the very personification of "the scaly

back of a reptile, and the horrible paws".

Yet, as intimated above, there is an anomaly, or oddity,

here.

Why didn't Lawrence disguise him more?

Why, in particular, didn't Lawrence, as he progressively

became aware of the full evilness of what Callcott represented,

go back over the manuscript and make it less obvious that

his erstwhile "mate" Jack Scott was the co-leader

of the Diggers-Maggies secret-army organisation (aka the

King and Empire Alliance)?

Why, to use an Australianism, did he "dob him in"?

Indeed, why were there no "backward revisions"

at all in the manuscript - the question that had worried

me back in the 1970s, when I first saw the holograph of

Kangaroo?

Surely Lawrence must have realised the danger he was putting

himself into...especially as he well knew that Scott and

Rosenthal and the rest would one day soon read the exposé

he was writing, literally, behind their backs.

Then the cat - or the scaly reptile with the horrible

paws - would be well and truly out of the bag.

One answer might be put down to Lawrence's notorious insensitivity

to the feelings of people he portrayed in his fiction.

Neville had remarked on this, and throughout his writing

career other examples abound. (How could he, for example,

have put the raddled character Lady Hermione Roddice into

Women in Love knowing how much it would offend

his loyal and supportive patron, Lady Ottoline Morrell?)

It was almost as if there was something in his method

of writing - his authorial technique, as it were - that

inhibited him from "interfering" with or questioning

how he converted fact into fiction, and its "automatic"

functions.

Yet there was another possible explanation that was emerging

from the research.

Maybe, like Victoria Callcott, the character Jack Callcott

was an amalgam of more than one person.

Maybe he was based on Scott plus somebody else.